Please find some common questions about the procedure below.

What is the spleen and what purpose does it serve within the body?

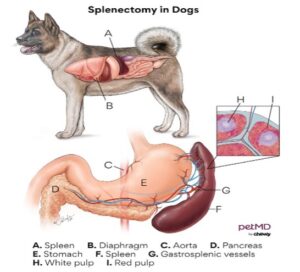

The spleen is located within the mid-abdomen of your pet (see image below). It functions to act as a storage bank for red blood cells and in the event of hemorrhage, the involuntary muscles of this organ will contract and release red blood cells into circulation. The spleen also functions to remove old, brittle red blood cells from circulation, or those infected with blood parasites (which is rare condition). The spleen is also part of the lymphatic system and functions to help bolster the immune system in fighting off pathogens like bacteria and virus.

What is a splenectomy?

A splenectomy is the surgical removal of the entire splenic organ. During a splenectomy, the entire spleen is removed by tying off/ligating the main blood supply to this organ. It is actually easier to control hemorrhage, and thus safer, to remove the entire spleen this way, as opposed to removing only a localized portion of the organ (such as the portion containing a mass or nodule).

Can my pet live without a spleen?

Absolutely! When the spleen is removed, the liver and bone marrow take over the roles of releasing new red blood cells into circulation, filtering damaged and disease red blood cells from circulation and bolstering the immune system with release of more white blood cells.

Why is my primary care veterinarian recommending removal of my pets’ spleen?

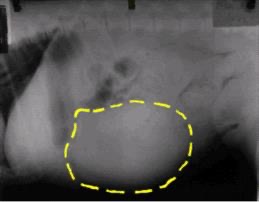

A splenectomy is advised in patients when splenic enlargement or a splenic mass/nodule is detected. Detection can occur during abdominal palpation on physical exam and/or confirmed on diagnostic imaging such as abdominal radiographs, ultrasound or CT scan.

There are two reasons splenectomy is recommended: 1. To avoid risk of splenic rupture causing bleeding into the abdomen (or to stop the hemorrhage if the spleen has already ruptured) and 2. To determine a diagnosis for the spleen’s enlargement or mass.

What patients are amendable to splenectomy in a mobile setting?

It is safe to perform a splenectomy at your primary care veterinarian’s office if your pet has cardiovascular stability. This would include any patients where the splenic mass is found incidentally, patients who are not clinical for anemia or for any free blood in the abdomen should it be present and who do not have any co-morbidities that make them at risk for anesthetic complications.

Patients who are affected by their anemia are at risk of needing a blood transfusion and thus should undergo surgery at specialty hospital with 24/7 aftercare. These pets are often weak and potentially unable to walk and have an elevated heart rate, pale to white mucous membranes, increased respiratory rate and low blood pressure. There abdomen will often be distended as well due to a large volume of free blood present within the abdominal cavity (hemoabdomen).

What are common differential diagnoses for needing a splenectomy?

The most common cause for recommending a splenectomy is because a mass or nodule was found on the spleen. Other disease processes that result in a need for splenectomy include splenic torsion, severe enlargement (usually seen in cats with mast cell disease) and in rare cases, splenectomy may be advised to better control immune-mediated disease.

If a splenic mass was found in my dog, does this mean my pet has cancer? What if there are multiple masses or a single very large mass?

Historically, veterinary research reported that approximately 2/3rds of dogs that present with a splenic mass will have an underlying diagnosis of cancer. In 1/3rd of cases, the mass is completely benign and surgery is curative. In recent years, some researchers have followed up studies on splenic masses with results supporting closer to a 50/50 probability of an underlying cancer diagnosis. Unfortunately, there is no way to differentiate if the mass is cancerous or benign without surgically removing the spleen and sending it to a pathologist to review a tissue biopsy. There is no definitive blood test that diagnosis splenic cancer and trying to collect a sample of the mass through a needle aspirate would only yield blood (and risk rupturing the mass).

The presence of multiple masses or a very large mass does not rule out the possibility of a benign disease process being present. In fact, there are numerous research papers that support that sometimes the larger the mass, the more likely it is to be benign!

However, there are potential risk factors that may be discussed during exam and work-up that may lead your primary care to feel that cancer is the more likely diagnosis. This includes older dogs, predisposed breeds (such as German Shepherds and Golden Retrievers), the presence of masses or nodules in other body systems and the appearance of splenic masses to be described as “target lesions” on ultrasound.

Why is my primary care recommending a full abdominal ultrasound and chest xrays before surgery?

Your primary care is recommending these diagnostics as part of a complete work-up for ‘staging’. Staging a disease is the process of looking for disease elsewhere in the body. Because the most common type of cancer that effects the spleen is a sarcoma, it tends to spread via the blood stream. If additional nodules or masses are noted in the lungs or liver, it is consistent with cancer being the underlying diagnosis, and the additional masses indicate that the disease has spread within the body. Therefore, surgery is usually not advisable in these pets due to the grave prognosis.

What are the most common types of benign and malignant masses in dogs? And in cats?

Benign masses in the spleen are often referred to as a hematoma. They are a collection of blood and clot under the splenic capsule that can form a mass-like effect. Underlying causes include history of blunt force trauma (hit by car, kicked by horse) or sites or extramedullary hematopoiesis or regenerative nodules that grow out of control.

The most common malignant cancerous mass is known as a hemangiosarcoma. This is a tumor of blood vessels and because blood is everywhere in the body, it has a high rate of spread (metastasis), most often to the lungs and/or liver.

Other tumors such as histocytic sarcoma and lymphoma are possible in the spleen of the dog but occur with less frequency.

In cats, mast cell disease and lymphoma are the most common cancers that affect the spleen. Hematomas are rare in cats.

What is the difference in prognosis between a splenic hematoma vs hemangiosarcoma?

With a splenic hematoma, surgery is curative!

Survival times with hemangiosarcoma are reported to be 3 months or less post-splenectomy and 3-6 months when splenectomy is coupled with chemotherapy.

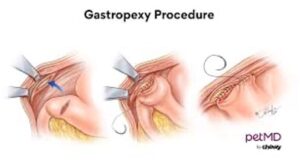

What are the indications for performing an elective gastropexy at the time of splenectomy?

Once the spleen is removed, more space exists within the abdomen to potentially predispose a dog to a secondary condition where the stomach twists along its axis, thus strangulating the blood supply to the stomach organ. This is known as Gastric Dilatation Volvulus (GDV) or bloat. Surgically tacking the stomach (via a gastropexy) to the right inner abdominal wall prevents the stomach from rotating on its long axis. A prophylactic gastropexy at the time of splenectomy may be advised in breeds predisposed to GDV (such as Great Danes, German Shepherds) and dogs that are deep chested. Deep chested animals often have a large amount of space within the abdomen that could lead to the stomach being more freely mobile without the spleen present.

The addition of a gastropexy at the time of splenectomy usually adds less than 15 minutes of surgical time and a nominal additional cost for the procedure.

What are potential intra and post-operative complications of a splenectomy?

Surgical risks include:

- Hemorrhage, including the risk for needing a blood transfusion

- Incisional swelling, bruising and infections

- Cardiac arrhythmias that may warrant additional monitoring and/or medications

- Sudden death, usually secondary to clot formation in the post-operative period

What post-operative restrictions are expected for a patient after splenectomy?

Once home from the hospital, discharge instructions will include:

- ACTIVITY RESTRICTION: Please keep your pet quiet and confined for the next 2 weeks. No running, jumping or playing until the incision is healed and the sutures or staples are removed. Short leash walks are fine for dogs. All cars should be confined indoors during the two week recovery period.

- INCISION CARE: Observe the incision daily for signs of redness, swelling or discharge. If any of these are seen, please contact your veterinarian for advice. An E-collar will be necessary to prevent licking or chewing at the incision. Alternatively, sometimes a t-shirt or surgical recovery suit can be worn instead of an ecollar to protect the incision. However, an e-collar is still advisable whenever not directly supervising your pet.

- SUTURE/STAPLE REMOVAL:

- If skin stitches or staples were placed, then a recheck appointment for their removal should be scheduled with your primary care 10-14 days following surgery.

- If the skin stitches were buried under the skin, they will absorb. However, 10-14 days of strict activity restriction is still required to ensure appropriate healing.

What long-term follow-up will be needed for my pet after splenectomy?

When a splenic mass is found to be benign on biopsy, no additional follow-up is needed and surgery is considered curative.

If a splenic mass is found to be cancerous on biopsy, consultation with an oncologist is usually advised. The oncologist will discuss additional care options that may include chemotherapy, or alternative modalities (which are ever evolving, such as the use of I’m-Yunity or Yunnan Baiyo)